Jan 13th. 2010

by Amelia Crater

Featured & UFO Phenomenon Do you recognize the word “TRONDANT” and know it has a secret meaning?

I don’t know who “them” are, but I do know the secret of TRONDANT. It was the “non word” used in the 1992 Roper Survey sent to 100,000 psychiatrists to give to patients who’d had “unusual personal experiences” i.e., “abducted by aliens.” Survey takers who said they knew the secret meaning of the made-up word were immediately eliminated from the study.

Don’t worry, you won’t be eliminated from this blog for knowing Trondant (But we will be keeping tabs on you ~ Ben). We know it’s not your fault; it’s not even their fault; it’s more likely his fault, Robert Bigelow, the camera shy billionaire behind BAASS, (Bigelow Aerospace Advanced Space Studies). He’s the man that funded the Roper study and has been attempting to corner the UFO market ever since.

Bigelow’s most recent conquest is outlined in this December FAA press release naming BAASS as sole repository of UFO sighting info:

“Persons wanting to report UFO/unexplained phenomena activity should contact a UFO/ unexplained phenomena reporting data collection center, such as Bigelow Aerospace Advanced Space Studies (BAASS) (voice: 1-877-979-7444 or e-mail: Reporting@baass.org)”

If your getting a odd, been-there-done-that vibe hearing this news, we’ve previously written about his suspected affiliation to shadowy para-government agencies as well as his public activities, and then last week Ben and Aaron beat me to this FAA scoop on episode 103 of MU+.

But wait, there’s more! With Bigelow, there’s always more to the story. In fact, this is the second time the FAA has passed the UFO hotline to a Bigelow funded institution. In 2001, the FAA directed UFO sightings to Bigelow’s now defunct National Institute of Discovery Science (NIDS):

“NIDS Becomes Only Official Organization to Receive UFO Reports from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) NIDS is pleased to announce that the newly printed Federation Aviation Administration (FAA) manuals indicate the National Institute for Discovery Science (NIDS) as the sole contact point in the United States to which the FAA reports UFOs.”

And just like now, in 2001 controversy likewise ensued:

Richard Boylan, PhD drboylan@jps.net 6-25-1 commented:

“The fact that NIDS gets a foot in the door with FAA under the Bush-Cheney Administration is prima-facie evidence that Dubya is a patsy, whether “witting” or unwitting, of Cabal assets.Bush has taken Republican “privatization” initiatives to new heights (or depths) by trying to “privatize” the UFO/ET contact phenomenon! Of course, he is only doing in a more public fashion what the Cabal has been doing for five decades — treating UFO/ET information, captured ET vehicles and individuals, and technology as private corporate property (sic). It looks like George W. will take us from the UFO Cover-Up to UFO-Privatization without ever going through the step of UFO Public Disclosure. Thus goes participatory democracy under President Bush II.”

It was also deja vu all over again when earlier this year Bigelow invested in MUFON, which he also did back in 1994. This time around he’s funding the development of a UFO rapid response STAR Team, which is slightly different than the pilot program he funded back in ‘94:

“Robert Bigelow suggested working with a coalition of U.S. UFO organizations comprised of MUFON, the Center for UFO Studies (CUFOS) and the Fund for UFO Research (FUFOR). By 1995, the groups involved had formed the UFO Research Coalition (URC), and they have continued working together on a number of very successful projects including the Ambient Monitoring Project aimed at measuring environmental changes during on-going abduction experiences.”

They may still be working together (although FUFOR’s hasn’t been updated since 2006), but if so, they’re doing it on their own dime. In 1995 Saucer Smear reported that Bigelow had packed up his greenbacks and gone home:

“Las Vegas businessman Robert Bigelow has terminated his financial help to the three major UFO organizations – MUFON, CUFOS, and FUFOR – due to ‘irreconcilable differences’. We are told that Bigelow wanted more control over how his money would be spent. We also hear that one leading ufologist went so far out of control at the final meeting with Bigelow that he had to be gently escorted from the conference room….Bigelow’s flirtation with the Offbeat is not over, however, as he is still apparently funding cattle mutilation investigation by Linda Howe…”

Yes, Bigelow has had quite a flirtation with the Offbeat, but it’s a romance that never seems to make it to the altar.

• In 1993, he started a radio program on the paranormal called Area 2000 with a Art Bell, George Knapp and Linda Moulton Howe, but cut off funding after the first year because he didn’t think they’d be able to continue attracting quality guests. Art Bell disagreed and Coast to Coast AM was born of the ashes of Area 2000.

• In 1995 he created the NIDS. Here’s what RedPill has to say about it:

“He created the National Institute of Discovery Science (NIDS) in 1995 to investigate border phenomena, stocking the advisory board with some of the leading lights in the field such as Jacques Vallee, Hal Puthoff, Melvin Morse and Edgar Mitchell. Employees of the organization were generally PhD scientists, as well as some former FBI field investigators and law-enforcement professionals. The NIDS website provides news and investigations into such wide-ranging topics as ‘Black Triangle’ sightings, cattle mutilations, consciousness studies and crop circles.”

• In 1996, he purchased the notorious Skinwalker Ranch, which is said to be riddled with UFOs, cryptozoological fauna, and hyper-dimensional portals to other realities. It was the the subject of countless articles and books at the start, but now it is strictly off limits results of any research has not been made public and it’s uncertain if Bigelow still owns the property.

• In 2004, NIDS was put into ‘in-active’ status in 2004 due to a lack of worthwhile cases to investigate.

Of course that was then and this is now. Sure, he’s got his space hotel project to fool around with, but you can’t expect a man like Bigelow to wait for ET to call reservations. And so, as Gizmondo reports, BAASS was born and they are hiring astrophysics, biochemists, microbiologists, nanotechnolgists, physicists, and propulsion and stealth technology experts.

“Bigelow Aerospace Advanced Space Studies (BAASS), a sister company to Bigelow Aerospace, is a newly formed research organisation that focuses on the identification, evaluation, and acquisition of novel and emerging future technologies worldwide as they specifically relate to spacecraft. BAASS is headquartered in Las Vegas, Nevada. We are seeking experienced scientists to join our research teams. If you are an inquisitive outside of the circle thinker, who is detail oriented and who is looking for a challenge, this is a unique and exciting opportunity to advance your career and to be a part of cutting edge research.”

So what’s up with this Bigelow dude that he starts things then gives up seemingly out of boredom or dismay, only to pick up right where he left off a year or two later? He doesn’t quit his actual business, not the Budget Motel chain, nor his Aerospace activities. He only disses his spooky interests. Why? Could it be ADHD? And what happens to all the data he amasses? Where do the UFO sighting reports go? Where did all the research from NIDS disappear to once the website was dismantled? If the scientists at BAASS discover the flux capacitor or anti-gravity propulsion, will the rest of the world ever find out? And how long will the Tang cocktails and reconstituted Eggs Benedict have to last beyond the day Bigelow decides space hotels are lame and cancels the return shuttle launch to pick up his orbiting hotel guests?

Of course, maybe he isn’t a flake at all. Maybe he acts the dilettante only to distract us from the massive knowledge base he’s creating on people, ideas, technology in order to…find ET…chart the unknown…inform the government…defeat death? Who knows? Only Robert Bigelow.

One person who had a early glimpse of Bigelow’s anomalous career is Dr. Angela Thompson Smith. She has written about her experience at the Bigelow Foundation in 1992 after she was hired as a liaison between the PEAR Institute at Princeton and the Bigelow Foundation. She ended up moving to Nevada and was on hand at the inception of many of the Bigelow projects discussed in this article. It sounds like a dream job. So although I’m not a physicist or engineer, I’d love to work for BAASS in a job like the one Dr. Smith had– investigating potential projects, conducting field research, and taking notes on what reality looks like while cashing paychecks drawn from the whirling vortex at the middle of the mystery.

Source: http://mysteriousuniverse.org

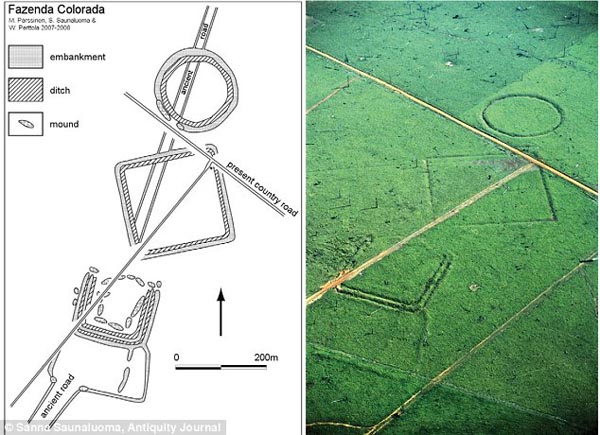

The Maya built pyramids. The Inca constructed Machu Picchu. But what do you know about the historical exploits of the Maléku, the Cabécar or the Bribri?

The Maya built pyramids. The Inca constructed Machu Picchu. But what do you know about the historical exploits of the Maléku, the Cabécar or the Bribri?